Contents

Overivew

Chief Scientist: John Collins

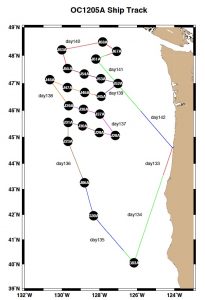

Dates: 12 May – 26 May, 2012, Newport-Newport

Objectives: Recover 23 WHOI OBS

Photos and Maps

Cruise Report & Fisheries Flyer

Leg 1 of the 2012 Cascadia Expedtions was succussfully completed. Details can be found in the cruise report:

Out at Sea: A Graduate Student’s Perspective of the CIET

Daniel Zietlow

PhD Candidate at the University of Colorado, Boulder

As a relatively new graduate student, making contacts with leading scientists in your field is not only a key for success, but also allows one to experience many unique and beneficial opportunities. In my case, one of the Chief Scientists of the Cascadia Initiative invited me along on the first leg of the 2012 field season. What follows is a brief account of my thoughts and experiences on this journey, which began in a small town in the Pacific Northwest.

Newport, OR and the R/V Oceanus

Newport is probably what you think of when you envision a seaside town still driven by the fishing industry. It’s small and people seem to know a lot about the ocean. We had a whole conversation today with our waiter about the conditions of the ocean and how in a small fishing boat this morning, the waves were pretty high. Hopefully, we won’t feel them that much in our ship. Our ship, the R/V Oceanus, is maintained and operated by Oregon State University, but owned by the National Science Foundation. I’m told that it’s less roomy than other research vessels, but what would I know. It still seems awesome. There is a well-stocked library to keep me entertained, plenty of food, and even a treadmill I stumbled across in one of the forward areas of the ship.

I didn’t have much time to explore Newport, but we did have dinner at a restaurant called the Local Ocean. Essentially, it’s a fish market in the morning, but restaurant at night. I had an incredible grilled salmon over a bed of linguine and vegetables. It made it that much more tasty knowing that it was fresh and alive just that morning (okay, a disturbing thought in retrospect, but who doesn’t like fresh seafood?). We pull out tomorrow for the open seas. Our current path will take us first south, just off shore California. We’ll then slowly make our way north into Canadian waters, then back track into Newport. Let’s hope for a successful expedition.

Out To Sea

My first task as a volunteer member of CIET made me feel like a lowly deckhand with scurvy: find coat hangers. It really highlighted my talents: search, attack, and deliver. Tomorrow, at least, we start pulling up instruments at which time I will be on deck actually hauling said seismometers out of the water instead of scrounging for hangers in people’s closets in order to hang up wet jackets.

After a breakfast of bacon, grits, and fruit (the food on board is amazing), we ran through safety drills. The fire drill was easy enough: if small, contain with extinguisher; if large, contain with door and get the hell out. The lifeboat drill was also just as easy, though involved running to your cabin to grab your life vest and then convening in the muster area. Then came the abandon ship drill. You had to get into an “immersion suit” as quickly as possible. Essentially, this was an extravagant dry suit designed to keep you alive after jumping into the frigid waters of the North Pacific. Needless to say, we ultimately would like to avoid this scenario. Too bad we didn’t get to actually practice the jumping overboard part. With the Captain declaring us competent, we slowly sailed out of Newport and left land behind. The sun was out and it wasn’t too windy, so most of us stood on the back deck and watched the Oregon coast slowly recede into the morning mist. We then turned south and set course for the first instrument off the coast of northern California, scheduled to arrive sometime in the morning. In the mean time, I ate a lunch of shrimp jambalaya with a Ruben sandwich (did I mention how good the food was?) and then attempted to get some of my own research for my dissertation done. Dinner brought us a dinner of spaghetti and meatballs with pork tenderloin. As a starving graduate student, I like that every meal includes two entrees, so it’s like getting two for the price of one. Though, the lack of exercise and the excess of food are going to catch up with me come two weeks from now.

Concerning the listing of the ship, it’s surprisingly having little effect on me. It’s more of an annoyance rather than a physical debilitation. It’s frustrating not being able to walk in a straight line or having the floor suddenly move out from under you, but provides for quite the harrowing adventure when you have to walk down a flight of stairs half the width of your foot. Well, I’m exhausted and headed to bed. I quite frankly don’t want to be responsible for cutting a line and sending a seismometer plunging back into the ocean tomorrow, so I had better be well rested.

Good Morning, Golden State

The thing about ship time is that it is very expensive. Thus, you work whenever you get to the next site, no matter what time of day it is. Our second OBS recovery of the cruise happened some hundreds of miles off the coast of Crescent City, CA at sunrise. It made for a fantastic backdrop, though I was exhausted having already been up for a few hours. That seems to be the tone of this cruise (for me at least): exhaustion. I don’t seem to be able to get a solid few hours of rest before I’ve got to be up again and out on deck for the next recovery. Surprisingly, this doesn’t seem to bother me at all. This is probably a good thing since the next week is going to be packed. Our first three seismometers were spaced relatively far apart, taking upwards of a day to get to them. Now, we have reached the densely spaced array of the deployment and these instruments are going to be popping up every few hours or so. So much for sleep. Better get it now while I can.

Wilson!

Depending on the type of instrument and depth of the ocean floor, it can take anywhere between 45 minutes and well over an hour for a seismometer to rise to the surface. For whatever reason, we were prepped to pull the next seismometer well before it had even left the seafloor, so we took the time to stand on deck and watch the sun set. I always enjoy being on deck, especially at the extremities of the day. It’s calming to be completely surrounded by ocean, watching some celestial ball of gas descend below the horizon.

While standing around taking photographs, two crewmembers suddenly walked out with poles and started poking at something in the ocean just over the railing. With my curiosity piqued, I too leaned over to see at what was being poked. It turned out to be a fishing float from who knows where. We amused ourselves for a good five minutes as they tried to pull this fishing float out (mind you, it’s round) with a pair of poles. Needless to say, it didn’t go well. The Captain finally walks out with a basket. You’d think that would have worked, but after almost losing said basket to the ocean, one of the OBS technicians walks over with another pole and somehow, with the three of them at it, they managed to pry this thing onto deck. We affectionately named it Wilson…I guess we have to amuse ourselves somehow.

No more than ten minutes later, we are informed that the seismometer has actually surfaced. I don’t think any of us have gotten to our stations that quickly before, not even during the abandon ship drill. Ah well, the instrument is safely on deck and we were given the rest of the night off. Mind you, our night still ended around 10:30PM…

I’m On A Boat…

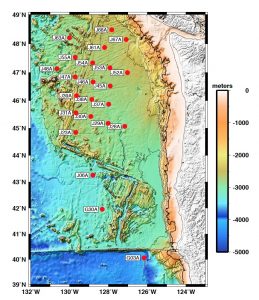

I figure it’s about time to explain what I’m doing on this research vessel. As some of you know, the Cascadia Initiative is an on-land/at-sea seismic and geodetic experiment investigating the megathrust subduction zone off the coast of Washington and Oregon. Essentially, we are worried about a large earthquake occurring in the western United States, the likes of which we have already seen in Sumatra in 2004, Chile in 2008 and now Japan in 2011. The Cascadia Initiative is a four-year experiment with the deployment of approximately 280 ocean bottom seismometers (OBSs) in about 160 sites across the Juan de Fuca and Gorda plates. My specific leg is collecting about 25 of these OBSs that were deployed last year so that they can be repositioned later in the year.

So, how do we pull an OBS out of the ocean? It’s rather straightforward. The OBS is weighted down by an anchor, from which we can release it via an acoustic signal (and a few other processes, but let’s not get into those details). Once it surfaces, the captain essentially drives the ship near the instrument, we attach some hooks to it via some poles, and then we can haul it onto deck utilizing a crane. My specific job is to either help with the tag line or get all the poles / ropes out of the way once the OBS is securely attached to the crane. Let me say that I was pretty worried the first time I tied a tag line in order to move an OBS around on deck. I just kept thinking, “please hold, please hold, please hold…” because if my line broke, the OBS would be freely swinging through the air. Fortunately, I have discovered that I am capable of making a solid bowline knot, so all of my tags have held. Once on deck, the OBS technicians debrief the instrument and I’m left in charge of cleaning and repackaging the radio antenna and flasher. The flasher is so we can see where the instrument is in the event that we recover it at night and the radio antenna is for hopefully obvious reasons.

Well, I’ve been up since 2AM and I’ve got to be out on deck again in about three hours, so I’d better get some sleep. Man, these days are starting to blur together…

O Canada!

We crossed into Canadian territorial waters over night. I’m not too sure exactly where we are, but something like 200 miles due west of the southern tip of Vancouver Island. The Canadian Pacific is a magical world, where the ocean is maple syrup and the clouds are the color of ice after a hockey game. The Canadian Navy greeted us the other day in the form of five watch seals. We assumed they were not hostile, but for all we know the seals are currently planning an attack of overt friendliness…yeah, I am going to hear about this from my Canadian friends. For the record, I actually do like Canada.

On a more serious note, we have been consistently coming across debris from the tsunami that devastated much of coastal Honshu after the 2011 Tohoku earthquake. At first, we thought the debris was just from local floats, but we have been looking up the company names printed onto the floats and have realized they are all Japanese based. Most recently, one of the floats that we recovered is printed entirely in Japanese characters. It’s actually pretty cool, if it didn’t carry a more sinister meaning behind it (as I’m writing this we just found a few more. We’re calling them “Little Wilsons.” I should also mention that we recover these floats since we don’t want plastic bobbing around in the ocean.). The scary thing about tsunami is that there is little one can do to prepare for one in the event that a large earthquake happens just off shore. Tsunami waves travel wicked fast, faster than we are currently capable of warning those along the coast of an approaching wave. It definitely gives our work a humanitarian angle. I know my undergraduate adviser always says that “scholarship is not justified by application,” but for the sake of my own sanity, I want whatever I end up doing in life to benefit society. I honestly have no interest in sitting in some office in an Ivory Tower, schmoozing with other academics when I could be out with a hammer rebuilding a fishing village. My work at both my undergraduate and now graduate institutions has definitely ingrained into me the concept of global citizenship. I’m incredibly grateful for that.

Having recently taken an Earthquake Engineering course, I have been inspired to pursue how I, as a seismologist, can get involved with designing safer buildings and promoting general earthquake awareness. Hopefully, after graduation I can get more involved with the design process…or go be Doctor for an aid organization.

Bringin’ Her Home

We somehow managed to do what should have taken 15 days in nine. All of the ocean bottom seismometers for which we were responsible are safely ratchet strapped to the deck and we are steaming towards Newport, OR. Well, steaming isn’t the word…leisurely floating at 8kts might be a more accurate description. I have really enjoyed this experience. Being cooped up on a small research vessel aside, it has been an incredible opportunity to venture outside of the bubble that is graduate school and accomplish something solely with my hands. I love waking up every morning (or the middle of the night) knowing exactly what I need to do and then going out and doing it. I felt the same way working for Habitat in New Orleans and I definitely feel the same way now. It is also refreshing to be doing something that we have technically been able to do for thousands of years: hauling stuff out of the ocean. The technology has certainly changed, as well as our safety practices, but we as humans have been sailing the seas since well before the start of the Common Era. No fancy computers or complicated algorithms involved. I have also developed a new respect for anyone who makes a living on the ocean or has endured a long ocean transit. Whether they are the pilgrims crossing to North America to escape religious persecution in Europe or the men and women of our Armed Services, life at sea can at times be rough. The fact of the matter, though, is that you have to just suck it up. Land is too far away and the time spent at sea too precious to just give up and turn back. It’s a nice metaphor for life: stuff happens…get over it.

Things I will miss:

- Simplicity

- Watching the sun rise/set while working on deck

- Standing on deck in high seas, feeling the acceleration as you rocket up and down

- Conversations while waiting for an instrument to surface

- Learning to tie knots between stations

- Not having to cook

- The feeling I get in the moment of pulling an OBS onto deck and realizing that I’m in the Middle of Nowhere, North Pacific

Things I won’t miss:

- The constant motion of the ship (I’m tired of bracing myself every time I brush my teeth)

- The size of the ship – I really need to go for a run

- Sleeping in a bunk that is too short

- Having to remember to tie everything down after using it

- The artificial lighting in the lab and hallways

At the end of the day, if asked again I would definitely agree to go back to sea. So, in the words of one of our OBS techs as we stood waiting for the last instrument to drift towards us, “let’s bring her home.”

Working in the Rain

Naturally, the otherwise decent weather we have been having for the past ten days gave way to a thick cloud cover and rain as we pulled back in to Newport. To be honest, it was at first quite strange being back on land. For starters, everything was still. After tying up to the dock, the ship rocked ever so slightly and I took a more-than-necessary step backward to compensate for a pitch of the ship that just wasn’t going to occur. Secondly, civilization seems to still exist. There are cars, and television, and cell phone service, and many other things that I did not miss all that much (okay, maybe cars). Much of today was spent working out on deck in the pouring rain. I can still vividly imagine staring up into the grey sky, an OBS high overhead with rain pelting into my eyes as we moved all the equipment back onto shore…it was fantastic. To me, it wasn’t miserable. It felt productive and reminded me that nature will always have the final say.

So, to everyone involved in this journey, thanks for a great cruise. It was great working along side of, and learning from all of you. And to all those hopefully reading this account, remember to take advantage of any opportunity thrown your way.