Dean here, reporting in English,

We’re sailing obliquely across the swells, bearing northeast towards the ‘hydrate ridge’ off of Oregon’s coast. These past 3-4 days have been tough, an unusual weather pattern settled in with a low stuck over California and a high over the Pacific Northwest. As a consquence, winds built out of the northwest to gale force, approaching 50 knots (that’s more than 50 miles per hour) and whipping the seas into a froth of confused waves riding growing swells.

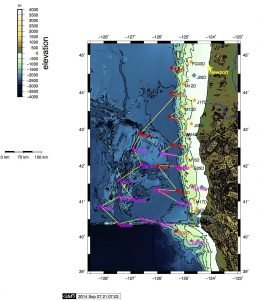

We had a spate of good luck early on, in that the rough weather we saw coming out of Astoria calmed down. We left deep water ocean-bottom seismometers for later and focused on the ‘TRMs’ (trawl-resistant mount) OBSs that were recovered from shallower water. Some of those involved Jason dives through spectacular sea life– a shark, squids, big ugly fish, thousands of brittle and sea stars, shrimp. Jason dove to the rescue for one ‘pop-up’ TRM when its buoy, attached to line attached to the OBS, didn’t pop up. So, just when our window of good weather was closing, we finished all but 3 of the 30 OBSs we sought to recover.

Then it became a game of cat and mouse with the growing, bad weather. Mostly, we were the mouse. We cruised north up the coast, sat on a site in rough seas where we couldn’t recover, then cruised north even more. We had a bit of weather where we gathered in the final three deep-water OBSs, the kind that drop anchor and float to the surface on sonic command.

We then beat our way out through growing seas to the site of a lost OBS. As with 2 cruises before us, we tried to communicate with that OBS (we do this with transponders that send sonic signals to it), but to no avail. We set up in different positions around it in case it was sitting on its side, restricting the directions in which it could communicate. The big problem was the weather, here we are in a ship equipped with Jason, and the seas were too rough for a dive. We pulled out of that lost OBS site and travelled N, again beating against high seas, and did similarly with another lost OBS. Again, many attempts from several positions and no communication. And, again, weather and seas too rough to call in the Jason cavalry to the rescue.

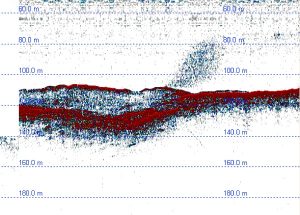

So here we are on our way back to port, via a ridge known for its gas bubbles. We’ll sit on that overnight and use the ship’s sound-based bottom-mapping system (swath bathymetry) to instead image gas bubble plumes as they rise over the ridge. We’ll pull off that site at about 3am and head back to the mouth of the Columbia.

General impressions: we made a few good calls early in the cruise regarding weather and where not to go next. These combined with long days allowed us to collect the 20 OBSs in the ‘pop-up patch’ near Eureka, CA and Cape Mendocino, and important geological feature where the San Andreas Fault, the Mendocino Fracture Zone, and the Gorda plate spreading center all meet. We pulled those up just in time. Then we fought weather to finish the original 30 and try to recover the ‘lost boys’ further out to sea. We imaged deep gas vents in various places. We got to sit in the Jason control van and take pictures, make notes, otherwise bask in the cool geek glory.

We’re worn out but happy. Year 3 of Cascadia is ready to transition from its third recover mission to its 3 deployment cruises later in the summer, where the ‘footprint’ of OBSs moves north to the coast of northern Oregon, Washington and BC. Hooray!